Since 2021, the University of Mississippi’s freshman class sizes have increased by 46% — from 3,584 to 5,240 freshmen in the 2023-2024 school year. Since the beginning of the fall semester, The Daily Mississippian has reported extensively about how this boom in enrollment is affecting the university community, from insufficient campus housing and longer lines for student union services to difficulty enrolling in already-full classes.

This unprecedented growth is a point of pride for the university, as it works each year to find new ways to accommodate more students. A university record 24,710 students enrolled across the school’s seven campuses in the fall. Still, many in the university community are asking the question: Why not just limit the number of students accepted?

Such a move would not be unprecedented.

In early 2023, the University of Tennessee’s Office of Undergraduate Admissions revealed that the number of first-year applicants had increased by a staggering 40.7%. This situation — a boom in first-year interest — should sound familiar. UT answered by reducing the number of students it admitted.

“To deliver the best Volunteer experience for all students across all four years and in course offerings, residential experience and student life, UT will reduce the size of its first-year class and enroll fewer first-year students than last fall,” UT’s Office of Admissions said in a public statement.

UT’s acceptance rate fell to 59.4% for in-state applicants and 33.3% for out-of-state applicants. Currently, UM’s overall acceptance rate stands at 97%. So, why hasn’t the University of Mississippi done the same?

Part of the answer lies in Mississippi’s statewide admissions policy, dictated in large part by a historic 1992 ruling from the Supreme Court of the United States: United States v. Fordice. The court sided with the plaintiffs, agreeing that Mississippi had failed to sufficiently desegregate its higher education system. The resulting settlement among the plaintiffs, the United States and the state of Mississippi — finalized a decade later — is colloquially referred to as Ayers.

Stemming from a 1975 lawsuit alleging unequal treatment of Black and white students in Mississippi’s higher education system, the Ayers settlement required the state to take strides toward leveling the playing field. One policy aimed at addressing this was statewide open admissions.

“The Ayers settlement originated from a 1975 lawsuit filed by a group of Black Mississippians, intending to address years of inadequate funding for the state’s three public Black colleges and eliminate barriers for students at predominantly white institutions,” Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning’s Director of Student Services Sandra Kelly said.

Litigation of the Ayers lawsuit continued until a settlement was finalized in February 2002. With the settlement came changes. The state agreed to make payments and invest in capital improvements for its historically Black colleges and universities, such as Jackson State University and Mississippi Valley State University, which were underfunded relative to their predominantly-white counterparts. In total, the state was ordered to pay $503 million towards equalizing Mississippi’s higher education system. Mississippi was also tasked with making its predominantly white education institutions more accessible to Black students.

“The nature of the case helped create more equitable educational opportunities in Mississippi by promoting a wider acceptance of open-admission policies,” Kelly said.

Currently, in-state students have access to all eight of Mississippi’s public universities, provided they meet certain criteria. The policy employs a sliding scale on which a combination of grade point average upon completion of the College Preparatory Curriculum, class rank and/or standardized test scores are evaluated to determine admissions eligibility. Even for high school students who do not meet the criteria, there is a path to education at Mississippi’s public institutions. Full details on the statewide admissions policy can be found on the IHL website.

This policy constitutes what is commonly referred to as “open-admissions.” For in-state students, admission to UM is mostly noncompetitive.

“I think it helped level the playing field for all students by providing multiple routes of admission and providing academic resources for students who might not have otherwise been admissible at our state’s public universities,” Jody Lowe, UM’s director of admissions, said.

Because of the statewide open-admissions policy, a cap cannot be placed on the number of in-state students admitted to UM. There is essentially no restriction on the enrollment of out-of-state students, as well.

“Over the last 20 or so years, the university has maintained relatively the same admissions standards for Mississippi students as we have for out-of-state students,” Lowe said. “We do have language in place that allows us to limit admission more for non-resident students if capacity dictates that we need to reduce out-of-state enrollment.”

It is not UM’s goal to decrease enrollment. Rather, it is relishing this period of historic growth. Conversations about restricting out-of-state admissions to alleviate pressure caused by enrollment are not on the table, according to University Marketing and Communications.

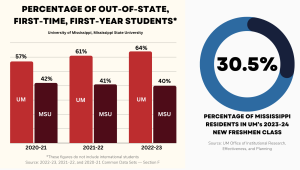

One reason may be that reducing the number of out-of-state students is not a financially tenable option. Of the 2023-2024 school year’s freshman class, only 30.5% of students were Mississippi residents. The remaining 69.5% of freshmen are non-residents, who pay more than twice the tuition charged residents to attend UM. Revenue from tuition and fees makes up 78% of UM’s operating budget, according to IHL.

Additionally, leaders in Mississippi and nationwide are turning their attention toward the impending drop in the number of high school graduates, which, for higher education institutions like UM, threatens to present the opposite problem: not enough students. With the knowledge that the pool of prospective students is projected to shrink, it would not make sense for the university to scale back its enrollment, out-of-state or otherwise.

As for next school year, though, UM is anticipating another year of strong enrollment.

“It’s too early to make any forecasts, but I would say that applications are very strong at this point for next fall,” Lowe said.

As part of the open-admissions process, the university will take applications for the 2024-2025 school year until the first day of fall classes.

Jim Zook, UM’s chief marketing and communications officer, assured that the university maintains a close eye on student experience and campus environment, pointing to the master leases and plans for new student housing as an example of ways UM is working to keep up with the rising student population. The university is constructing new student housing on campus – three residence halls will be built on the site of the recently demolished Kincannon Hall – in addition to a parking garage to accommodate more students.

The Ayers settlement was intended to last through mid-2022. Though it has since expired, the open-admissions policy is unlikely to change.

“The university system is committed to empowering various learners, which can be achieved by ensuring educational opportunities are accessible to all students,” Kelley said. “Therefore, open-admission remains secure. Currently, IHL and academic leaders are collaborating to evaluate the existing admission standards to streamline processes for enhanced effectiveness.”

John Sewell, IHL’s director of communications, noted that the board of trustees has not engaged in discussions regarding amendments to its minimum admission criteria.