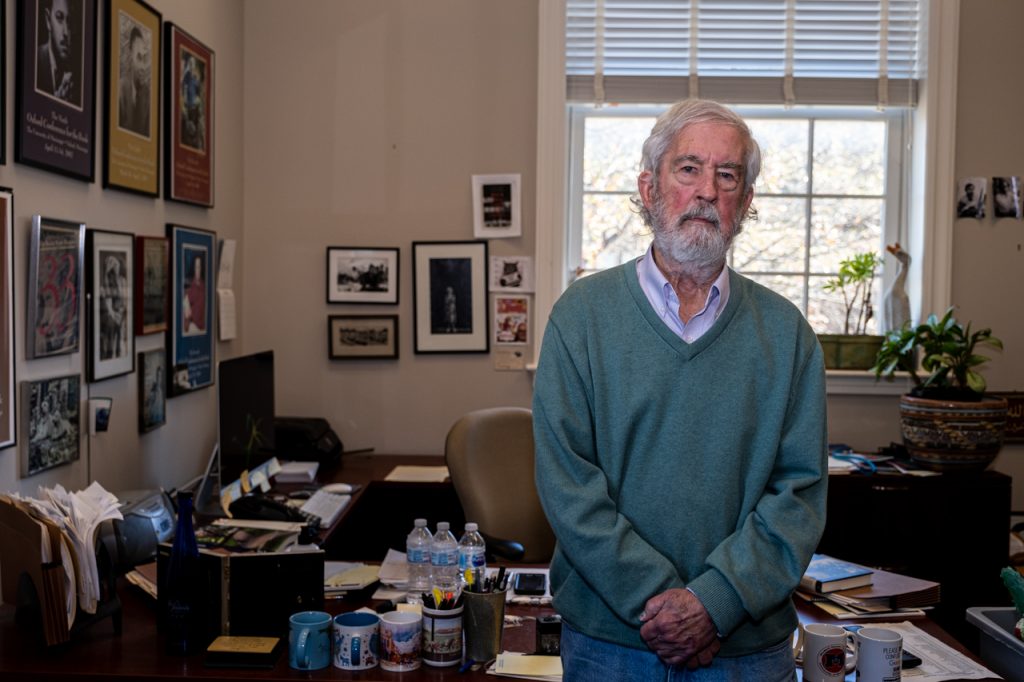

Curtis Wilkie grew up at the University of Mississippi. As a child, he lived in a family dorm as his mother worked to earn her Master’s degree. His father served as the chief of campus police, and his great-grandfather was a student when the Civil War started. It was no shock when Wilkie decided to attend the university himself in the late 1950s, and when he returned as a professor in 2002 after retiring from The Boston Globe, “it was like coming home.”

“It wasn’t a long-range plan at all,” Wilkie said. “I was hanging out here during football season in 2001, so fully a year after I retired, and I was approached by a guy who was chairman of the journalism department, which was way smaller then. He asked if I would be interested in teaching as an adjunct, and I thought, ‘Well, I don’t really have anything else to do, and it might be fun.’”

Wilkie has taught as a journalism professor ever since — besides a semester-long stint at LSU. Now, over 18 years later, he is retiring from teaching.

“Your whole life is kind of a learning experience, but I’ve learned a lot from my students,” Wilkie said. “I don’t know how good of a teacher I am now, but I hope I’ve improved from this guy that took over with really no training or expectations I’d be doing this.”

To that point, Debora Wenger, interim dean of the School of Journalism and New Media, said Wilkie sets the standard for someone who has deep expertise, incredible personal humility and a genuine love of story-telling and teaching.

“From the first minute that I had to interact with Curtis one-on-one, I was always a bit nervous,” she said. “I’ve been around a lot of journalists over the years, but someone who operates at the level that Curtis does can be intimidating. Still, he always makes you feel as though your story is as important as anyone else’s.”

After his final class on Tuesday, Nov. 17, Wilkie joked that the reason he has fought retirement was because he doesn’t play golf, but ultimately, he said, “It’s just time.”

Wilkie also said the COVID-19 pandemic made it easier for him to leave the university. Before March, he would arrive at his office in the Overby Center at 6 a.m. five days a week, but this semester, the pandemic has reduced his on-campus time to two days a week.

“Now, it’s kind of like a mausoleum, so it’s not like I’m leaving a really wonderful thing. Hopefully, we’ll have it back at some point, but it’s kind of just sad and dispiriting being here, not much life on campus,” Wilkie said. “Otherwise, it’s been a great experience.”

In his time as a student and then as a teacher, Wilkie has seen the university transform from a segregated school with approximately 3,000 students who were mostly from in-state into what it is today.

He was a student at the university in the fall of 1962 when James Meredith enrolled, and he witnessed the riots that broke out across campus as a result. Since graduating from the university in 1963, Wilkie said UM has “changed indefinitely.”

When he returned to campus as a professor, he saw the band ceasing to play Dixie, the ditching of Colonel Reb, the removal of the state flag and the recent relocation of the Confederate monument.

“I wouldn’t have come here and taught if it had been the same school that I attended,” he said. “Probably, the most important thing to me is to see the progress that’s taken place here racially. Not to say that it’s perfect. We’ve still got a ways to go, but it has been encouraging to see, almost every year that I’ve been here, more and more Black students from Mississippi are choosing to come here and excelling, being outstanding students.”

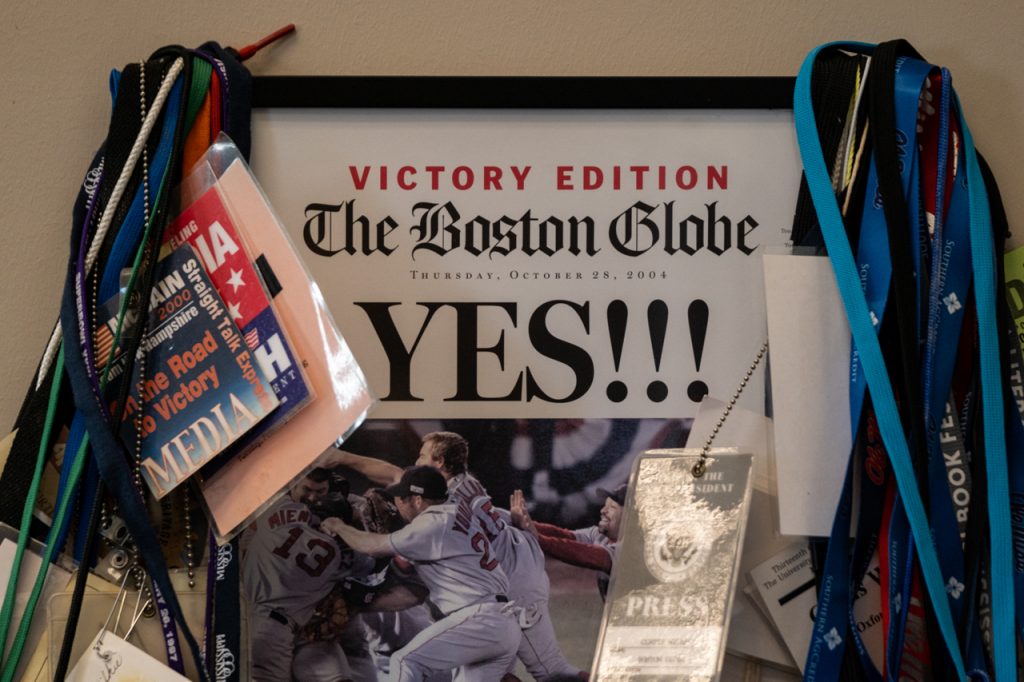

Wilkie covered the civil rights movement in Clarksdale as his first job after graduating, and said that time has been his “frame of reference” for the rest of his life. As he moved to Boston, Washington, D.C., and abroad, Wilkie became known for his critique and coverage of the South, and he attributes his ability to do so to growing up in Mississippi and attending UM.

“I’ve tried not to be a professional Southerner,” he said. “But I think being a Mississippian gives you, certainly, a very valuable perspective because we are, I think, the most fascinating region in America. There’s so much conflict and change that goes on here. It’s a dramatic place to live and work, and I’ve always enjoyed Southern stories.”

While Wilkie said he is unsure of whether he’ll continue writing those Southern stories now that he is retiring, he is looking forward to the publication of his sixth book, “When Evil Lived in Laurel: The ‘White Knights’ and the Murder of Vernon Dahmer” this spring. The book centers around the Ku Klux Klan and South Mississippi in the 1960s.

He also plans to continue living in Oxford.

“This is my home,” he said. “I’ve got family that lives next door to me, and my daughter, her three sons, my son-in-law. I’m here.”