Samir Husni has 37 years of experience at Ole Miss, witnessing the ups and downs of the university over the years, which could explain why amidst a world-changing pandemic he has maintained an incorrigible optimism about voluntarily teaching face-to-face during these unprecedented times we’re in.

A professor of journalism and director of the Magazine Innovation Center, Husni has been teaching his classes in a hybrid format. Once instructing a full auditorium of 180 students, now he can only have 34 students on Tuesday and another 34 on Thursday. He declares that nothing can hinder your true calling as a teacher, not even the pandemic. Adapting to the new normal, with its masks, social distancing and frequent reapplication of hand sanitizer, is part of the job.

“No, no stumbling blocks,” he said, “no walls, nothing, because at the end of the day, you’re the bridge that’s going to connect yesterday with tomorrow, but you have to be building this bridge today.”

Husni’s determination and resilience reflect similar attitudes from others in the university community who are committed to adjusting to the post pandemic world of higher education and recognizing how changes in accessibility, communal support, and the network of departmental communication are the keys to transforming the university for the better.

“…It has been a year of…tremendous stress and change and adaptation,” George McClellan, associate professor of higher education said. “I think it’s important that we all recognize that and that we…celebrate the strength that has been reflected. But also be completely empathetic and understanding of folks…”

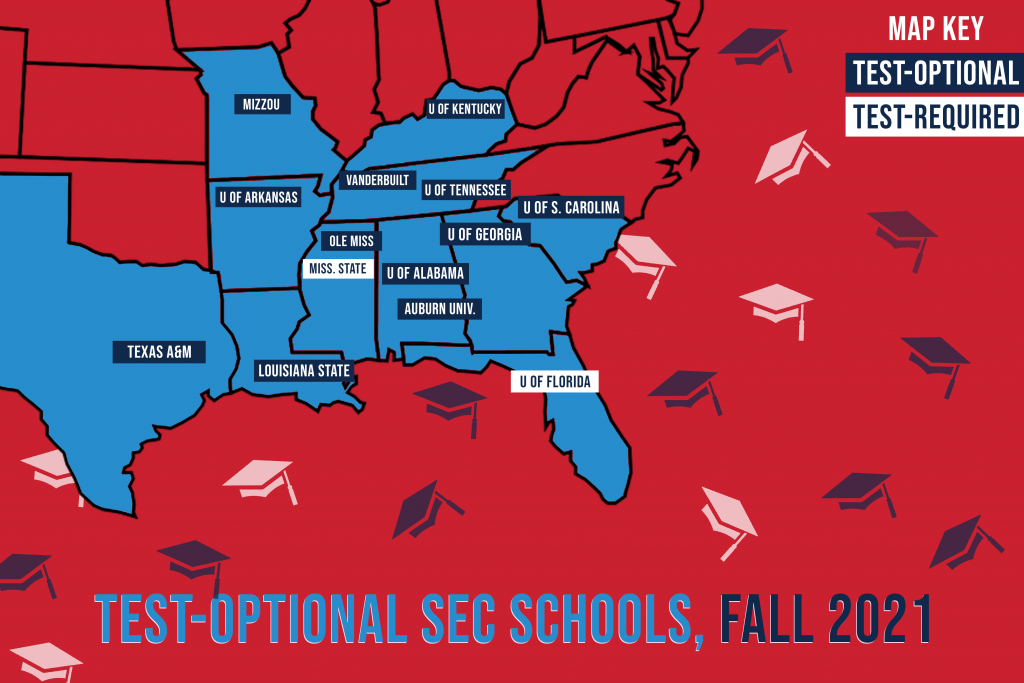

McClellan says rethinking the university’s admissions process has the potential to radically change who has access to higher education in the state, including Black and indigenous people of color and those of lower socioeconomic statuses — communities who have been most impacted by the pandemic.

“There’s a real opportunity here to take this disruption that has been presented by the virus and really move the institution in the ways that I sometimes hear people say they want it to move,” McClellan said, “but I don’t always see behaviors that match the verbiage… There’s an opportunity here for us to seriously rethink how we recruit who we recruit, how we package aid, all of that.” In particular, McClellan says that the university could pursue virtual recruiting over traditional processes to better discover more diverse people in cities and rural areas. Also, the economic disruption that is likely to continue into the near future could produce post-traditional age people looking to find a new career or middle-class people who’ve stretched their resources because of the pandemic, he says. And he suggests that the school could revisit offering institutional aid to students strictly pursuing a degree online. “Are we going to use [this opportunity] to rebuild the past or create the future?”

Macey Edmondson, another graduate associate professor with a doctorate in higher education, agrees, saying that some equivalent of her department elimination GRE requirements could be done at the undergraduate level for incoming freshmen and transfer students.

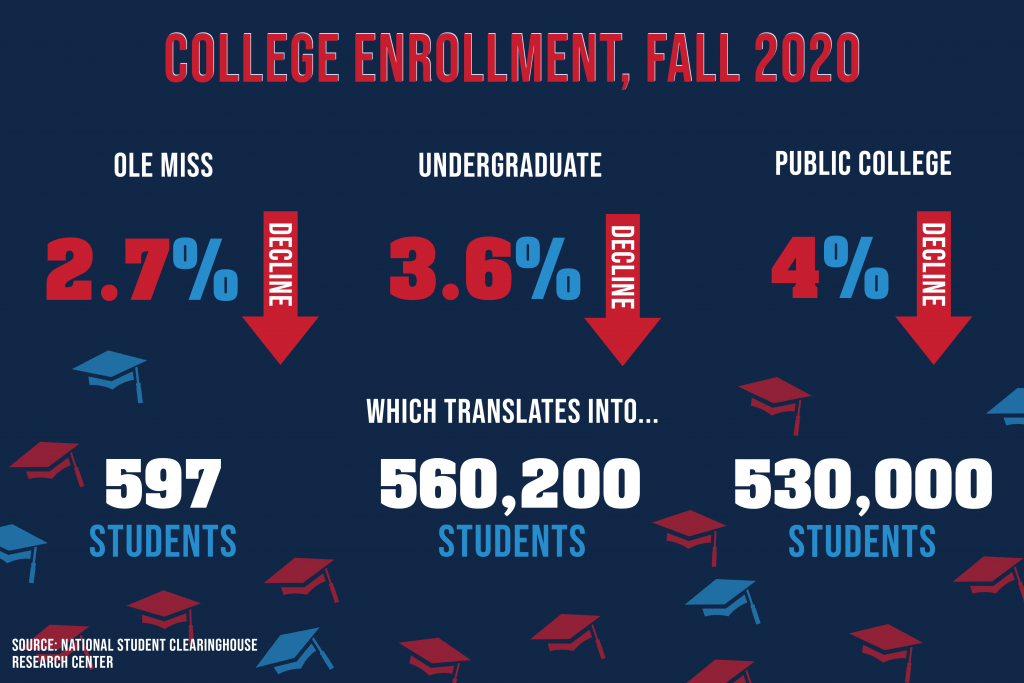

Even before the pandemic, more colleges have been eliminating standardized tests as a requirement for applying. According to The Hechinger Report in 2019, one in four schools stopped requiring the ACT and SAT, and at least 41 institutions had done so in that year alone. Besides these tests, at times, being a hindrance to students without the resources to properly study for them, in 2020, the mandatory cancellation of test dates left students who would have taken these exams without results.

The two professors also addressed the importance of catering to students who are not interested in the traditional college experience, one not only centered around education but also tethered to an environment of social activities and shared living. Some students have a life that exists off-campus.

“So if anything, I think that we learned we need to be flexible really quickly,” Edmondson said, “that things don’t have to be so entrenched that we can’t make changes. …in the end, what we all wanted was for students to be able to get their education, right?”

Edmonson says that flexibility ultimately makes college more accessible, another important facet of the collegiate experience, especially for disabled students. Attending class from the comfort of your own home through Zoom has its benefits, especially for disabled students who, in the past, may not have felt fully able to fully participate in school. It is also fantastic that students who have limited movement or can’t handle crowds can go to class without having to traverse an entire campus, according to Edmondson. However, she clarifies that others may suffer from the lack of routine because some of them work best in a face-to-face setting.

“It’s hard having to do everything online,” first-year graduate student Maggie Bushway said, “but for disabled students it’s actually a little bit easier because online learning gives us the opportunity to, like, stay home, if we need to. And people are more considerate about our needs right now.”

Bushway has an autoimmune disease called Sjogren’s Syndrome, which causes seizures and requires the help of a motorized wheelchair due to nerve damage. When talking about accessibility before the pandemic, she said that her professors did the best they could with the resources they had to provide her the necessary accommodations.

“But I think that it could have been much better with, like, virtual learning,” Bushway said. “So, I wish that it had been there when I was doing my bachelor’s degree, but I’m thankful that I have it for my Master’s.”

She also discussed how the pandemic is making more people sensitive to disabled people’s issues, saying that it’s not hard for a professor to record a class for students who are unable to come, and she hopes that awareness remains after the pandemic, especially as a high-risk individual.

“Students who are high risk,” Bushway said, “should be able to always have the option of learning online, or learning in class because we’re high risk, and so sometimes it’s like putting us in a dangerous situation to have us go to a class that’s, like, 300 people in it.”

Lilly Herring is another disabled student who appreciates the accessibility of digital learning but still faced challenges in adjusting to attending class on Zoom. Having Golden-Harr Syndrome, which affects her heart and hearing, captions are necessary for her to properly learn in class. In her experience, not many professors have taken advantage of Zoom’s live captioning feature. Others have used Google Meet, which also has live captioning, uploaded lectures to YouTube, which has auto-captioning, or used other third-party services to accommodate her.

“I can’t always understand what they’re saying,” Herring said, “and so, if I miss it, I miss it, and so, I really have to, like, try to find friends or rely on another classmate to make sure I have the notes correct. So, that’s been kind of difficult.”

As such, Herring has always been able to rely on Student Disability Services, which helps accommodate disabled students at Ole Miss. As the university has become more aware of the issues of accessibility in a digital learning environment, according to Stacey Reycraft, director of SDS, her department has also been learning to provide newer accommodations.

“Some accommodations transfer easily to an online environment; others are more complicated,” Reycraft said in an email. “We’ve had to be more creative… Many students have requested additional accommodations that were not needed when they were taking face-to-face classes.”

For students like Herring, SDS could provide a note taker who passes those notes to the professor, who then could provide them to students who couldn’t hear the lecture very well. She emphasized that services like this and captioning are accommodations that benefit everybody in the long run.

“Our main focus is just that there are ways that put us on equal planes with everyone else,” Herring said. “It’s only going to help because the playing field that was leveled for disabled students, I think that is only going to get better.”

What’s more, students and teachers alike have championed new initiatives at Ole Miss to further support one another. Inspired by the pandemic, these new developments have the possibility of being mainstays for the future.

“I think [the pandemic has] forced us to be resilient in a different kind of way,” Dr. Natsha Jeter said. “It’s forced us to realize and understand we’ve got tools and resources, strengths we didn’t even know that we had. We’ve had to rely on those things and come together in a way that we’ve not had to do so before, and I think that’s important.”

Jeter is the Assistant Vice Chancellor for Wellness and Student Success at the university. Essentially, she constantly assesses how the culture here at Ole Miss can be further optimized for the well being of the student body.

For instance, one of the changes that Jeter hopes stays after the pandemic is the availability of telehealth and telemental health services that allows people to get help without physically being on campus. Other people at the university are studying technology’s role in mental health, particularly during a time of limited face-to-face interaction.

“I got interested just in general in all of the different ways that technology allows us to feel heard and feel like we belong,” Graham Bodie, a professor of integrated marketing and communication with a doctorate in communications, said.

He has recently started working on a study of students’ mental health using the app HearMe, a text-based conversation app wherein people can confidentially connect with Listeners, people who will provide a digital shoulder to lean on and hear your worries. Students can login with their university email and immediately seek a Listener or volunteer as one at their institution.

Through a series of surveys that will be distributed throughout the semester, Bodie’s study seeks to gain a general understanding of students’ emotions, especially about seeking support from others online.

Also, agreeing that COVID had a significant influence on this study, Bodie wants it to be able to expand the sources of support on this campus. Considering that social distancing protocols may interfere with a student’s ability to connect with the Student Health Center or Psychological Services Center, this app could help supplement those avenues and provide another option. Ultimately, he thinks HearMe could help destigmatize reaching out to better your mental health.

“Your ability to de-stress and find ways to cope with even the minor and the daily hassles that we have to deal with,” Bodie said, “that is an important component of mental health. And so, if you don’t have anyone to talk to… There’s this app that you can then burden somebody you don’t even know.”

Apoorva Mate, however, took a more direct approach to find support that catered to her specific needs. As a disabled grad student, she feels the graduate experience has unique pressures that needed a different kind of support that she couldn’t find. Born out of the sense of isolation of the pandemic, she recently founded the Organization for Graduate/Professional Students with Disabilities and Chronic Illnesses.

“I started this organization that, base level, for me, was where we could vent our frustrations freely,” Mate said. She clarified that also their goals are to bring awareness to and hold professors accountable for the unrealistic expectations that hold disabled students to, even during the pandemic.

Mate, being a PhD student in math, also believes that while not an exclusive experience, STEM fields especially have a problem with the rigorous study expectations and pressure to publish research. According to her, she’s heard of professors encouraging disabled students to retake their class at a later time because they couldn’t accommodate them currently or even question the validity of a student’s diagnosis.

“You cannot expect us to just have, like, 10 cups of coffee to function,” Mate said. “That’s not how it works… Some of the things I want professors to realize is, don’t lower your expectations from us because we are completely capable… But, I just want the timeline for us to be a little different.”

To keep professors accountable, Mate eventually wants to work towards getting questions added to teacher evaluations that explicitly ask how the professors addressed accommodating students, training for professors, and awarding professors who they felt best helped to fulfill student’s accommodations.

Keep Teaching, formed in March 2020, is another initiative inspired by the pandemic that was originally meant to help with the abrupt shift from physical to online learning, but it grew as the needs of faculty and administrators did during the pandemic, according to Robert Cummings, executive director of academic innovation and an associate professor of writing and rhetoric.

“It’s really designed to bring people together to share information of how to be better teachers in the middle of a pandemic,” Kathleen Wickham, professor of journalism, said. The topics addressed include internet access, home working conditions, Zoom skills, Zoom fatigue, and effective teaching practices.

Wickham and Cummings are both professors and a part of Keep Teaching, only one of a number of resources borne of last Spring’s shutdown to assist acclimation to digital education. Others include Keep Learning and Keep Discovering, which provide student resources and general COVID-19 resources, respectively.

“I believe that a lot of my colleagues during the course of this have come to realize that it’s a lot more important to focus on what people learn and how they learn it and not the deadlines by which they learn,” McClellan said. That can include extending deadlines by a week because of a death in the family, which McClellan has done, or Edmonson allowing her students two weeks to work on class modules, giving their lives room to function around coursework.

Hear what McClellan also says about the pandemic changing the student-teacher dynamic.

Departmental lines have broken down in service of collaboration. Educators from diverse areas can share their worries and offer guidance to one another. Administrators have been able to respond faster to their needs because of these meetings, Cummings said.

There is definitely a place for Keep Teaching after the pandemic.

“We tend to be in our silos,” Wickham said. “…We don’t really get a chance to sit down and have a casual conversation about teaching. And yet we have so much to learn from each other. So I think I hope it will continue when we get back to traditional teaching.”

Hear how she says she will be a different teacher post-pandemic.

Husni says that the Internet is a breadth of information that students can access, but only in-person lessons can help curate and comprehend the real, helpful information.

“I’ve made the adjustments,” Husni said, “but at the end of the day, I mean, there’s nothing better than looking the students in the eye, and they’re looking you in the eye. That’s the only thing they can see from your face these days is your eyes.”

Whatever issues there were with keeping students engaged, he feels that they are even more so these days. Utilizing tried-and-true methods, Blackboard discussions and randomly calling on students in class, he forces students to stay diligent, counteracting that eight-second attention span for an hour and 15 minutes.

“You have to be part comedian, part educator, part police, part big brother, and part just their age, a teenager,” Husni said.

Jeter maintains that the university as a community is stronger together.

“I think as long as we continue to listen to one another, we continue to talk…” she said, “it doesn’t mean we’re not going to have conflict. If we continue to work through and navigate conflict in a way that’s responsible and respectful, we will continue to make strides and be on top. As long as we work together as a team.”