Mandatory COVID-19 vaccination has been a hotly debated issue on college campuses since students returned to classes in August.

Even though the state Institutions of Higher Learning board this week notified student workers they will be required to show proof of vaccination, with exceptions, by Dec. 8, the IHL has for months steadfastly stated that it would not require the general student population to be vaccinated for the virus in order to attend classes. The IHL’s recent requirement came only in response to a federal mandate requiring vaccinations of all people who work with federal contractors, many of whom are university faculty, staff and student workers.

This is starkly different from the response to a measles outbreak on campus in 1992.

In that instance, unfamiliar to many current members of the university community, students and staff born on or after 1957 were required to receive their second dose of the measles vaccine or they were not allowed back on campus.

Monday, Feb. 10, 1992, became a memorable day for Dr. Eric Dahl. There were two confirmed measles cases on campus. At the time, Dahl was the acting director for the Harrison Student Health Center at the university. The official director was on a cruise during the weeks of the measles outbreak, leaving Dahl to call the shots.

A week prior, Dartmouth College had seven students die from measles. The university did everything to prevent such an event from happening.

“Everybody was working 14 hour days. We would vaccinate at the Coliseum. We would vaccinate at the Student Union, and so we are getting cooperation from all the Department of Student Affairs personnel,” Dahl said. “Sparky Reardon was the assistant director and was instrumental in encouraging students to look at this serious event. There’s no reason people can’t die here.”

There are two forms of measles: rubeola, which lasts for one to two weeks and can lead to life- threatening complications, or rubella, which is only dangerous to pregnant women.

After those two cases were confirmed, the Mississippi State Health Department officially declared an outbreak on campus.

Any students who didn’t comply with Health Services were not allowed to go back to the classroom, until they had proof of vaccination.

Following this announcement, the university quickly transitioned into vaccinating everyone who could not prove that they had received their second dose of the measles vaccine.

Students who had received their second dose were directed to go to the Student Health Center to check their immunization status. If they had been vaccinated against measles twice prior to arriving on campus, they would receive a card imprinted with the Student Health Service seal.

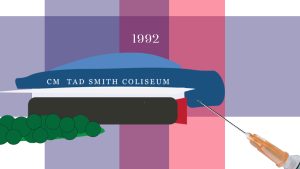

Those who had no proof of receiving two shots of the measles vaccine were sent to receive their second dose at the Tad Smith Coliseum Wednesday, Feb. 11, 1992 from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. There were 50 nurses on site giving the vaccine to people.

Shots were also given that Thursday, but the university encouraged students to receive their second dose Wednesday, due to high demand.

The Tad Pad was fitted with rows and rows of tables. Half of the tables were designated for records, while the other half were vaccination tables. Because students were required to have proof of vaccinations, the Tad Pad had lines wrapped around it of students and staff waiting for their shots.

The only people who were exempt from the immunization requirement were those allergic to the vaccine, pregnant or those who received their second dose of the vaccination after their first birthday.

Dahl said the side effects of the vaccine were far less severe than a possible case of measles. The side effects usually were no worse than a high fever.

“Classic measles (rubella) is characterized by a bad cold and progressively increasing fever over a period of three or four days, red eyes and a cough,” Dahl said.

The other form of measles, rubeola, resulted in fever as high as 104 degrees and redness of skin.

Fortunately, the university cases were classic measles, or else there would have been more hospitalizations.

Donald Dyer, now the associate dean of the college of liberal arts, was a Russian language professor at the university in 1992. Dyer recalled the outbreak on campus and the vaccination process.

“I remember I wasn’t a real big fan of needles back in those days, and I was going, ‘what’s the cut off going to be on age?’ I’d rather not have to get one of these if I don’t have to. And unbelievably, guess what the cutoff date was? 1957. I was born in ‘58,” Dyer said.

He then recalled walking over to Tad Pad from Bondurant Hall, where he taught his classes. During that time, shots were delivered through a gun, rather than the needle syringe that is used today.

“So you just walked up, you know, rolled up your sleeve, and they put the gun next to your skin and shot it.” Dyer said.

Attorney Walt Davis was an Ole Miss law student at the time of the measles outbreak. For many law students, it was a struggle to retrieve their proof of vaccination. Davis, in particular, had his records mailed multiple times to the University Medical Center from Mississippi State, his undergraduate institution, but the records could never be located. Eventually he had to receive the vaccination on campus to continue to go to his classes. However, Davis was not as fortunate as other students who received the vaccine. He experienced adverse effects, caused by a genetic predisposition.

“Within 48 to 72 hours, I had a severe inflammatory reaction, an arthritic reaction where I couldn’t stand, was on crutches for several weeks and had to use a cane for about six months after that,” Davis said. “I lost about 35 pounds in a month and had to go through several doctors in several tests to figure out exactly what was going on. So I wound up attending class on crutches for most of the rest of the semester and using a cane through the summer and into the fall.”

On Thursday Feb. 13, 1992, only 3,000 students were cleared Wednesday for Friday classes, leaving 6,000 students yet to be cleared to attend classes. At that time, there were still two confirmed measles cases, but a rise was expected to happen in the next week.

The rise happened on Friday, Feb. 14, with a spike up to 15 confirmed cases. At the end of the two week hiatus due to the measles outbreak, a total of 9,000 students were cleared to return to classes with 7,000 students receiving a vaccination on campus.

“Ninety percent of the students have endured the inconvenience,” Dahl said in a 1992 edition of the Daily Mississippian. “From the bottom of our hearts, we thank them.”

Almost 30 years later, the university faced a similar viral outbreak: COVID-19. In the spring semester of 2020, students were sent home, due to both the fear of contagion and the uncertainty of the virus. The university has had 1,860 cases since March 16, 2020.

Dahl explained the transmission process of the measles compared to COVID-19.

Contagions are classified by “R-naught.” Dahl said he would describe HIV as a 4, meaning if one person gets HIV, they are likely to give it to four people. Influenza is rated a 2, and the new Delta variant is an 8 and a half. Measles, however, is highly contagious. The R-naught can be as high as 20, especially in dormitories.

COVID-19, Dahl said, is different. Because COVID-19 is a relatively new virus, doctors are still conducting research to see how COVID-19 affects a large spectrum of people. However, there is another factor involved, Dahl said. The political nature of the country has evolved over the past 30 years.

Dahl said that the most major contrast he has seen between the two outbreaks has been the reluctance to receive the vaccine.

“I think there was far less severe resistance in ‘92 to getting the measles vaccine. It was kind of like, oh, you know, what a hassle,” Dahl said. “Now, there are folks who have bought into the conspiracy theories to the point that it’s a fervency like nothing I’ve ever seen in medicine. And it’s just a shame that politics have been rolled into medicine, and I don’t blame either party.”

Davis also said that the change in political climate contributes to the contrasts in how both outbreaks are handled.

“The appeal toward the base of both parties is different than it was previously, the primary traditional fights between the conservatives and the liberals.” Davis said. “You know, in the ‘90s, we’re still talking about social welfare programs, military spending and things we’d all grown accustomed to. We grew up during the Cold War.”

Davis said that people did not have the luxury or time in the 1990s to worry about whether or not vaccination mandates were a violation to one’s rights.

Dahl used a metaphor for the measles vaccine and the COVID- 19 vaccine, comparing the two to speakers used to play music.

“If you stream music on your iPhone now it’s perfect music. It’s the most sophisticated source of recorded music you can get,” Dahl said. “In my childhood, we had records that played at 78 RPM on a scratchy little box, and the music was really poor quality and scratchy. And I would liken that that’s what an old measles vaccine is like. And that this modern streaming is what the COVID-19 vaccine is like.”

Until recently the university, the Mississippi State Department of Health and the Institutions of Higher Learning were not requiring students or faculty to show proof of COVID-19 vaccinations. However, on Oct. 25, the IHL announced that all faculty, staff and student-workers of any public Mississippi university or college are required to be fully vaccinated by Dec. 8, with exemptions.

Caron Blanton, IHL spokesperson, commented on the parallels between the measles outbreak and COVID-19 and how the Board responded.

“Unlike 1992, the State Health Officer has not asked the Board to mandate the COVID-19 vaccine,” Blanton said. “The State Health Officer has asked the Board to encourage all members of the campus communities to get vaccinated, which the Board of Trustees and the universities have done through communication efforts, incentives and providing opportunities for students, employees and community members to get vaccinated.”