When Melinda Sutton Noss, former university dean of students, was transitioning out of her role last spring, she remarked that if a new chancellor were to be hired before she left, she would have worked for five different chancellors within five years.

Noss took over as dean of students under Chancellor Dan Jones, who was replaced in interim by Morris Stocks, who was replaced by Jeffrey Vitter, who was replaced in interim by Larry Sparks. Six months after Noss’s departure, the university hired its 18th chancellor, Glenn Boyce.

For reference, in the 20th century, the University of Mississippi had nine different chancellors over a 100-year period. Since 2015, five different men have occupied that seat in the Lyceum.

At the time, Noss said the turnover in the Lyceum didn’t affect her ability to effectively carry out her job, but noted that “it does take time to build relationships and get to know people and understand their style and what may be a priority for them.”

However, the revolving door of university leadership is not reserved only to the highest-paying leadership position in higher education in Mississippi.

Since 2015, when Jones was ousted as chancellor following a dispute with the Institutions of Higher Learning Board of Trustees over control of the university’s medical center, the landscape of university leadership has changed drastically.

Of the 14 individuals that constitute senior leadership at the university, 10 were either hired or promoted during the past four years. Among the changes are: Interim Director of Athletics Keith Carter, Chief Legal Officer Erica McKinley, Interim Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Charlotte Fant Pegues and Provost and Executive Vice Chancellor Noel Wilkin.

During that time, the director of admissions, the assistant vice chancellor for student affairs, a head football coach and a head basketball coach also either had been fired or retired from their positions.

This revolving door of faculty transitions begs the question: Is this a problem for the university?

Sutton Noss and Leslie Banahan, former assistant vice chancellor for student affairs, say no; Provost Noel Wilkin said the same. However, all three either work or previously worked in the Lyceum, where much of the turnover occurs.

In an email response to The Daily Mississippian, Provost Noel Wilkin said that the university is a “sum of all of its people.”

“As a result, how a student experiences the university is more dependent upon the interactions with the faculty and staff than it is a function of the chancellor,” Wilkin said.

He continued: “The university relies upon the chancellor to cast a clear and concise vision that motivates everyone to pursue the next level of success as we pursue our mission. The vision motivates people to work toward our goals together. This drives advancement, improvement and success in each area of our institution.”

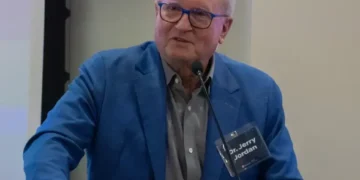

George McClellan, associate professor of higher education in the School of Education, is an expert in the field, having previously served in various leadership roles ranging from vice chancellor for student affairs to vice president for student development at universities across the country. He has also published dozens of books and articles about higher education systems and institutions.

He said high turnover can cause a litany of issues within a university but also opportunities for growth.

“In an ideal situation, you don’t want to see that much turnover in a short amount of time because you can get institutional corruption, but it also presents a fairly significant opportunity,” McClellan said.

Changes in leadership offer university presidents and chancellors the opportunity to restructure departments and change the philosophy of a university. In any field, leadership changes can breed wholesale turnover in departments, and university governance is no different.

“Sometimes the chancellor, he or she will come in, and they will say very quickly, ‘I want my team.’ Rarely do you see them come in and wipe out a whole team at one time,” McClellan said. “Although sometimes it happens; it’s not that common because that really hurts your own presidents. But it’s not uncommon to see all of the turnover within a year to two years.”

He added that the process used to select Glenn Boyce “will affect our faculty hires because people will wonder about shared governance at the university. People who might otherwise be attracted to vice chancellor jobs will be, I don’t know. That (process) looks like a mess.”

However, the University of Mississippi is not unique in experiencing turnover atop the leadership ranks. According to McClellan, the average tenure of a college president is roughly five years. This development is a product of the increasing scale of public institutions and the politicization that follows hundreds of millions of dollars being invested into a business. These developments lead to employee burnout, which shortens tenure and leaves universities in a near-constant state of flux.

Of the other seven Mississippi public universities governed by the IHL Board of Trustees, four (Jackson State, Mississippi Valley State, Mississippi University for Women and Alcorn State) have appointed new presidents or chancellors since 2017. Delta State and the University of Southern Mississippi have had their current presidents since 2013, and Mississippi State’s President Mark Keenum assumed office in 2009.

McClellan said that in states with hyper-politicized higher education systems, turnover is rampant. He didn’t classify Mississippi as such, but said, “Mississippi — in particular, the University of Mississippi, because of its actual and symbolic importance in the state — is a particularly fraught environment.”