The state college board took seven months to select a new chancellor following former chancellor Dan Jones’ ousting in March 2015. It’s been just two weeks since Chancellor Jeffrey Vitter resigned from the same position, but many in the Ole Miss community already have their eyes fixed on the future.

Jones’ and Vitter’s legacies are temporally separated by less than a year but are emotionally far removed from one another.

Days after Jones announced his departure in 2015, students crowded the Circle waving signs and shouting slogans of dissent. In the two weeks since the November morning Vitter confirmed his impending resignation, campus life has rolled along without protest, campaign buttons or national attention. Things are different these days.

“A lot has happened since 2015,” said Rev. Gail Stratton, who retired this past spring after 21 years as an Ole Miss biology professor. “The election of 2016 happened, and with that, (there have been) many more protests happening on campus. The biggest protest on campus was to protest the firing of Chancellor Dan Jones.”

Since the end of the Jones era, an enrollment boom has leveled out, the football program has taken a few hits and campus construction has been a constant. The university has also earned its first Carnegie R-1 designation, congratulated its first female Rhodes Scholar and begun hosting an annual tech summit.

Nearly four years after the March 2015 protest over Jones’ contract debacle, the campus environment is different, and the challenges in finding the university’s next chancellor appear to be a new kind of beast.

How were they different?

Dan Jones’ letter announcing his departure from the Lyceum sounds more critical than the farewell letter released by Jeffrey Vitter on Nov. 13.

Vitter’s expression of surrender and acceptance clashes with Jones’ sentiments of defeat by and disappointment with the IHL’s decision not to renew his contract.

In his Nov. 13 farewell letter, Vitter wrote that “the time is right for someone new to take the helm.” Vitter will resign in January and take a faculty position in the School of Engineering, a return to his foundation in computer science.

“There is no more important role on a university campus than as a faculty member,” Vitter said in an IHL press release.

Jones felt differently about his departure, and the former chancellor made sure to let the student body know where he stood. He expressed sadness and referenced his unwillingness to conform to the state government’s will.

“I very much wanted to continue to serve for another four-year term, and I am disappointed that will not happen,” Jones wrote before rejecting claims that his departure was a result of health concerns. He began treatment for lymphoma in November 2014 at the university’s medical center.

In 2015, the IHL faced the challenge of replacing a well-loved chancellor who did not want to go. The board and university are now approaching a more modern challenge in finding a candidate who can bring balance to a university community looking for stability.

What makes a chancellor?

Months into the 2015 search process, the state Institutions of Higher Learning surveyed Ole Miss community members on what mattered to them in the search for their next chancellor. The IHL heard from 1,903 community members, ranging from prospective students to retired staff members, about the university’s strengths, challenges it faced and the qualities sought in a new chancellor in Sept. 2015.

To those who responded, money was a major concern.

The poll showed that 70 percent of the Ole Miss community members surveyed were concerned with declining state appropriations. Fifty percent of respondents said the university was challenged by a “lack of infrastructure to support growth,” and 45 percent were concerned with faculty compensation.

If the IHL based even a small portion of its selection process on the results from that poll, the board would likely have been keen to seek out a chancellor who could bring in some much needed funding. However, Vitter seemed to struggle with increasing access to state-appropriated money during his time here.

Last spring, Vitter joined the seven other university presidents from the IHL system in lobbying the state legislature for increased higher education funding. The IHL had lost more than $107 million in state-appropriated funding since 2016 at the start of the 2018 fiscal year.

Vitter did lead the university into new territories of research funding, and fiscal year 2018 saw a 23 percent increase in external research funding on the Oxford campus.

Of the nearly 2,000 Ole Miss-affiliated subjects surveyed during the 2015 chancellor search, 70 percent identified themselves as alumni. Today, some Ole Miss alumni have identified cracks in the university’s foundation beyond its finances.

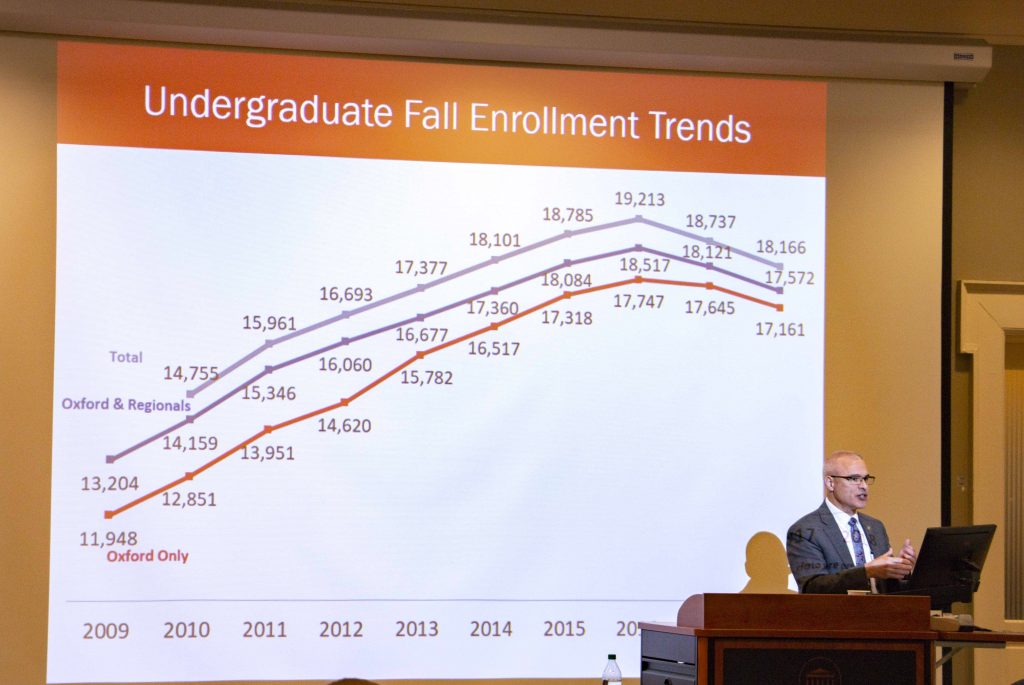

“I’m mostly concerned about our drop in enrollment,” said Hayes Dent, who graduated from the university in 1989. “At a time when universities are kind of blowing and going, I’m a little bit concerned about those numbers that I see.”

Between fall 2003 and fall 2013, enrollment on the Oxford campus climbed from 12,950 to 18,427. Since then, the student body’s growth has stalled out. Enrollment on the Oxford campus has decreased between fall 2015 and fall 2018, and freshman enrollment across all University of Mississippi campuses declined 6.5 percent from fall 2017 to fall 2018.

“Mainly it’s this situation around a drop in enrollment, which, of course, gets the financials of the school messed up,” Dent said.

Dent is the founder of Stand Fast Ole Miss, a group representing a faction of the Ole Miss community that feels that the university has lost sight of the values of free speech and academic freedom. The group came together months before Chancellor Vitter announced his resignation in response to what they see as an increasingly reactionary campus environment.

“I’m also concerned that people who might be conservatives are not particularly welcome on Ole Miss’ campus right now,” Dent said. “That’s just a personal opinion. That’s just how I feel about what I see.”

Dent said he hopes to see Ole Miss reposition itself similarly to how other schools rooted in the South, such as the University of Alabama or the University of Georgia, have done in years past. He said the university could benefit from focusing its efforts away from analyzing its past in favor of building a future like those schools have.

“It seems as if Ole Miss is constantly mired in focusing on the past and contextualizing everything, and what we ought to focus on as a university is the future,” Dent said. “We ought to focus on what role the university can play in the development of Mississippi, in its health and economy.”

Stratton said much of the university’s growth this decade can be attributed to a focus on moving forward and “shedding of some of the Confederate symbols.”

“There were important steps of moving forward, and I truly think that as that happened the university became more and more attractive to more and more students and more and more funders,” Stratton said.

Stratton’s time at the university was one of rapid growth and infrastructural improvements, down to the sidewalks and buildings on campus. She remembers the university taking strides to improve its appearance, both conceptual and physical.

“(When I arrived) it looked like it hadn’t changed for about 30 years,” she said. “Now there are so many new buildings, the Ford Center and the expansion of the stadium.”

An evolving campus like that of today’s Ole Miss will likely continue to find itself stepping into new territory while hoping to hold on to the values that made the university what it is.

“The next chancellor, as every chancellor has had, will have this important dance of moving the university forward to be fully in this century,” Stratton said.

A state-run search

Twelve IHL board trustees appointed by Gov. Phil Bryant hold near-total control over the selection of the university’s next chancellor. During the hiring process, the board has the ability to seek input from a Campus Search Advisory Committee made up of Ole Miss community members, but that committee’s direct involvement is at the discretion of the IHL board.

“I think the feeling around the last search was that there was not that much transparency, and there was a feeling that the university community did not have enough input,” Stratton said.

The search process begins when the IHL board forms a Board Search Committee made up of trustees and selects a commissioner from amongst themselves to lead that committee. If that committee declines to use an expedited process to select a known candidate, the search process opens to applicants.

In 2015, the IHL Board Search Committee partnered with a consulting firm based out of Dallas to find a chancellor for Ole Miss. Then Board President Alan Perry worked with the firm to present candidates to the Campus Search Advisory Committee, but said IHL trustees’ opinions could differ from the campus committee’s.

“We have a lot of information through our consultant that the Campus Search Advisory Committee doesn’t necessarily have,” Perry told the Associated Press in October 2015.

Per the IHL’s bylaws, the Campus Search Advisory Committee reviews all applicants received before an advertised date, and its members are required to individually and confidentially submit recommendations and votes for five candidates. The IHL board reviews these votes and determines which candidates will be interviewed. After two rounds of interviews, the board will select a preferred candidate to visit campus and interview with various groups affiliated with Ole Miss.

The last Campus Search Advisory Committee consisted of 34 representatives of the Ole Miss community. The majority of members were alumni, among other affiliations, including then Mayor Pat Patterson.

Oxford’s current Mayor Robyn Tannehill is also an alumna of the university and will likely be included on this year’s Campus Search Advisory Committee. She was not involved in the search process in 2015. Tannehill said she hopes the IHL will select a chancellor who understands the unique relationship between the city and the university.

“I do hope that the search committee places a high priority on seeking a leader who understands the importance of building community,” Tannehill said.

The IHL board will spend the next months navigating a field of applicants tinted by an array of often contrasting interests in who will be the next chancellor of Ole Miss. Regardless of their opinions of Chancellor Vitter, people in the university community want to see someone bold step into the Lyceum this year.

“Somebody who’s tough as nails…,” Stratton said. “A very skilled negotiator, a communicator who is committed to moving forward.”

Dent said in founding Stand Fast Ole Miss, he wants to start a conversation about building upon already positive aspects of the university.

“The ultimate goal of this group is to convince our College Board to name a Chancellor for Ole Miss who will not only pay lip service to these values (of free speech and academic freedom) but has a proven track record in his or her professional life that demonstrates a deep belief and understanding of these concepts,” Dent wrote on Nov. 9.

Regardless of who fills the role, the next chancellor of Ole Miss will have to earn the community’s trust before beginning to balance its many wants and needs.

“These are hard conversations, and those hard conversations take time, ” Stratton said. “Through building relationships, learning to trust, learning to hear about different experiences and sitting with that discomfort.”