Stolen and thrown into the Tallahatchie River. Replaced. Shot. Replaced. Shot again.

This was the fate of of the Emmett Till memorial marker until Saturday, when a new memorial was dedicated to the civil rights martyr.

The sign was designed to be as resilient as the legacy of Till himself. It weighs 500 pounds and is made of stainless steel, protected by a layer of bullet-proof glass. A motion-sensitive security camera sits below to keep watch over visitors and any would-be vandals.

With a cotton field on one side and the edge of the Tallahatchie River on the other, over 50 people gathered around the marker for the rededication ceremony. This spot, known as Graball Landing, is where historians believe that Emmett Till’s body was pulled from the river 64 years ago.

The new sign is the fourth erected by the Emmett Till Memorial Commission since 2008. The second sign was riddled with 317 bullet holes by the time it was replaced in 2016. The third sign only stood for 35 days before being shot again.

The same week that the fourth sign was done being built, a photo emerged that showed three white University of Mississippi fraternity members posing next to the vandalized sign with guns, grinning ear to ear. The photo was posted on one of the members’ Instagram profiles before making national headlines in July, following a report by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and ProPublica.

Though a complaint about the post was filed to the university in March, no statement was made about the post until after the story broke. This was because of the mishandling of the university’s investigation, according to the university. The only punishment the students received over the racist incident was a suspension from the Kappa Alpha fraternity.

Speakers at Saturday’s ceremony included two of Till’s relatives and other advocates determined to keep his memory alive.

Dave Tell, author of “Remembering Emmett Till,” told the story of civil rights activist Betty Pearson and a letter she wrote to a friend in 2007 about the reasons for putting up Till’s first sign.

“She said, ‘I’m not putting up signs to make sure we get the facts right, and I’m not putting up signs to increase tourism or to save a town by bringing tourists dollars in. I’m doing this because these signs make new kinds of conversations possible,’” Tell said.

Pearson was present for all five days of the Till trial, in which an all-white, all-male jury acquitted the two men accused of Till’s murder. According to Tell, Pearson said that between 1955-2007, she never once had a conversation across racial lines about Till’s murder.

“So the sign is not just a sign, right? By giving dignity to the story, we’re hoping it makes new kinds of conversation about racial reconciliation possible,” Tell said.

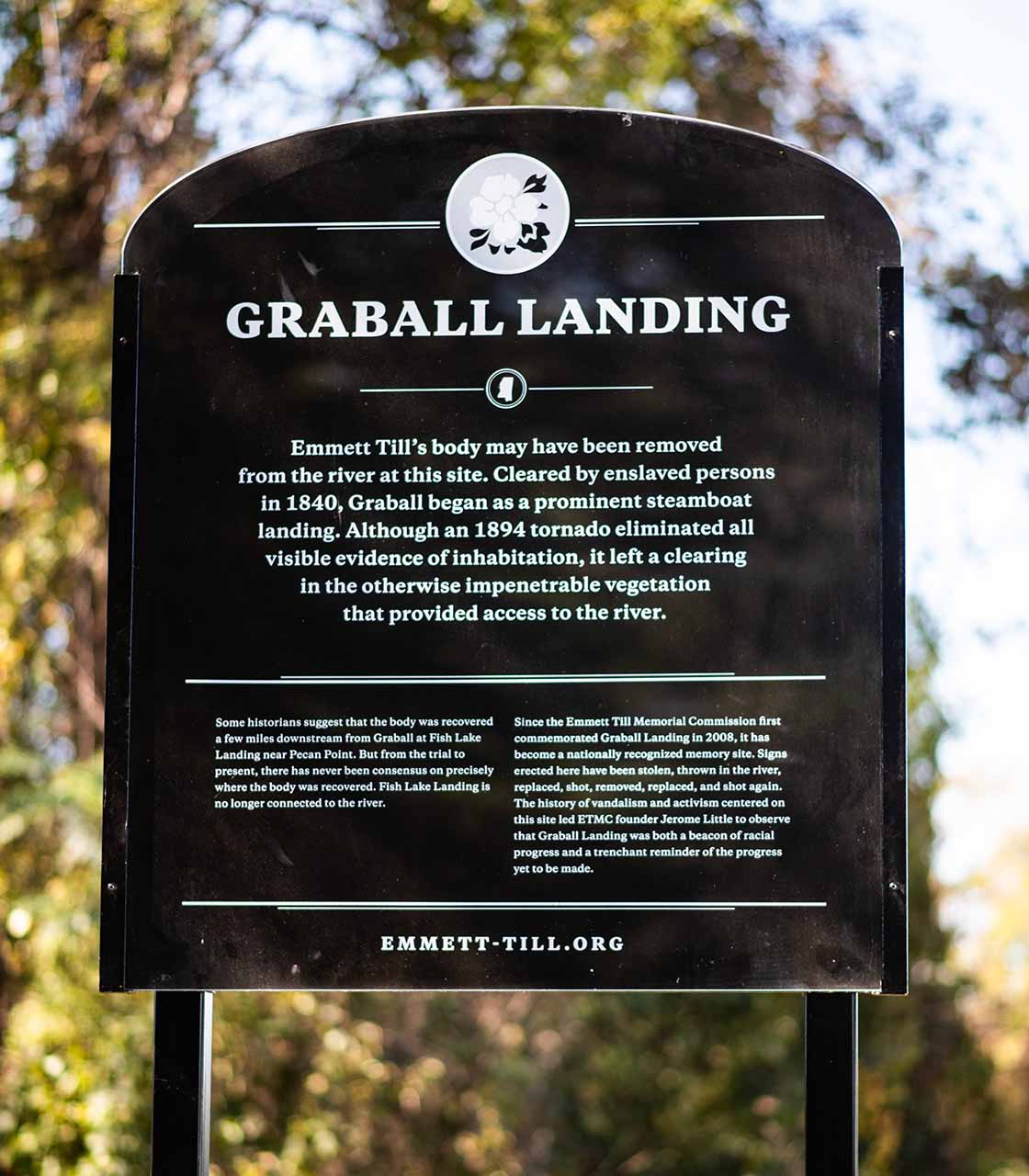

For the first time, the Till sign includes the story of the previous vandalism. It’s part of the story, too, and the people involved with its construction think that in order to reckon with what happened in 1955, one also has to reckon with what’s happened since then.

“We understand that racial reconciliation begins by telling the truth. Our historical markers allow a first step towards that truth-telling process. Sadly, there are still those who want to deny the events of 1955. We cannot change our past but we have a responsibility to tell our stories together so we can move forward together with a shared future,” Patrick Weems, Director of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center said.

The new additions were also meaningful to Till’s cousin, Airickca Gordon-Taylor.

“I’m so glad that they have incorporated what happened with the other signs. To me those bullet holes are symbols of the constant murder of young people across America since 1955… Mississippi wants you to forget who Emmett Till was. Our family will not allow that to happen,” Gordon-Taylor said.

In 1955, then- 14-year-old Emmett Till left his home in Chicago to visit family in Mississippi. During the trip, a white shopkeeper, Carolyn Bryant, accused Till of making sexual advances toward her at Bryant’s Grocery in Money, Mississippi. Four days later, Bryant’s husband, Roy, and his half-brother, J.W. Milam, kidnapped Till from his uncle’s home. They then beat him, shot him in the head and threw his body into the Tallahatchie River.

The jury that acquitted the two murderers only deliberated for 67 minutes. Carolyn Bryant admitted decades later that her claims Till harassed her were lies. Roy Bryant and Milam didn’t wait nearly as long to admit their crimes, doing so in a 1956 interview with Look Magazine, as their acquittal provided them double jeopardy protections.

After Till’s mutilated body was recovered from the river, his mother, Mamie, famously demanded an open casket at her son’s funeral so others would have to confront the horrors inflicted on him.

Gordon-Taylor gave half of her speaking time on Saturday to her mother, Ollie Gordon, who showed reverence to Mamie.

“We can’t tell the story of Emmett without the mother. The mother fought to keep his death from not being lost and not being without a cause. This is what spearheaded and boosted the civil rights movement. I am sure that she’s looking down on us today, and I am sure that she’s honored that so many people have a love for her son. That they continue to fight for justice,” Gordon said.

Following the ceremony, a reception was held a few miles away in Sumner, the town that holds the Emmett Till Interpretive Center and the courthouse where Till’s murderers were tried. In front of the courthouse, two objects stand as reminders of Mississippi history. On one side of the entrance is a marker for the Emmett Till murder trial. On the other is a monument for the Confederate soldiers of Tallahatchie County, where it has stood since 1913.