Once, while in college, I was at a track meet watching a race with a teammate and good friend of mine. In the race, one athlete’s heel was clipped by another’s, and the athlete went tumbling down. “Man,” my friend said, “that guy got jewed over.”

I paused in disbelief. “What?” I said sharply. He giggled a bit sheepishly, knowing he had made a mistake. As a Jewish man from New York, I had never even heard that. I do not think my friend, who probably had not been close to a Jewish person before, connected the term “jewed” with a real human being. To him, it was just a saying.

But I didn’t let him keep saying it. I let him know that it is not at all okay to use that phrase. I still love the guy — and this incident didn’t change how much I care for him one bit — but I did not accept his behavior just because he is my friend.

I can believe that, for some people, Confederate symbology and language may not be directly connected to the harming of others; regardless, it is not at all acceptable. The Confederate emblem should be removed from the state flag. The statue in the Circle has got to go.

And we have got to stop saying “Ole Miss.”

Language matters, but we often get used to saying things that normalize harm. Certain phrases diminish or denigrate groups of people, and if not addressed, these phrases become so commonplace that those using them do not even consider their origins and effects. “Jewed over” is one example, as are the Washington “Redskins” football team and –– one I just recently learned about –– “lame,” which can be hurtful to people with disabilities. And there is a big one, known nationwide, linked to the University of Mississippi.

When I first came to Mississippi, I didn’t know anything about the phrase “Ole Miss.” However, I have since learned that it was used in the time of slavery in reference to a plantation owner’s wife.

The retirement of this term would surely upset a great deal of people, many of whom also know nothing of the name’s origins. For many, the term may genuinely have an innocent meaning.

I get it, but I don’t get it. The miracle of the United States is people living side by side with others from races and places and cultures perhaps as varied as anyplace else in the world. Yet, as we inhabit each others’ spaces, we sometimes fail to really, truly see each other.

Accepting the term “Ole Miss” as inevitable demonstrates sympathy for people who would be hurt because one of their school’s nicknames and traditions would fall by the wayside. What about others who could be affected by the normalization of the phrase? It is a reference to slave-plantation life that implies fond nostalgia.

There may be no college campus more suitable to lead a movement to disassociate the virtues connected with the Confederacy. While being “Ole Miss,” this is also the alma mater of James Meredith, who in 1962 became the first black student at the University of Mississippi. His enrollment led to a riot in which two people were killed. Doing away with the term “Ole Miss” would be a small step to continue his and this university’s legacy. I am not the first person to suggest this name change, but I am happy to be an advocate.

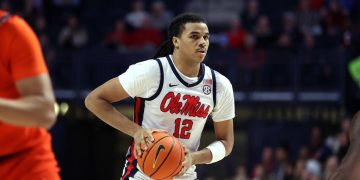

We could start by boycotting any business –– in Oxford or elsewhere –– that sells merchandise bearing the term. We could petition the university’s sports teams to order uniforms that do not bear the nickname.

With eleven syllables, “The University of Mississippi” does not exactly roll off the tongue, and a nickname is surely in order. The replacement is so obvious that it is staring us directly in the face: let’s call it “New Miss.” This would acknowledge the past, honor the tradition, but turn it in a way that is oriented toward honoring the experience of all students and people.

In discussing this and similar matters with friends, I have heard it suggested that we are choosing between being hypersensitive or belligerent, but I don’t see it that way. It is not about worrying about every word we say or punishing ourselves for our mistakes. It is just about respecting each other as much as we can. This is a simple contribution to that cause.

Zach Borenstein is a second year Masters in Teaching student from Scarsdale, New York.