What do you do when your history has been erased? You create your own.

In “The Watermelon Woman,” Cheryl Dunye’s groundbreaking debut film, autobiography and fiction are weaved together to create a stunning portrait of Black lesbian history, spanning the 1930s to the 1990s. What is the news peg for this story? Is the film being shown here at Ole Miss? Is it newly released on streaming? Essentially, why are we publishing a story about an 18-year-old movie?

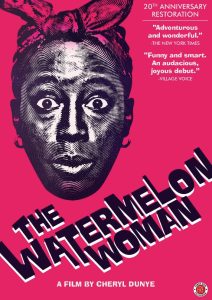

Released in 1996 and added to the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry in 2021, “The Watermelon Woman” is the first movie directed by a Black lesbian. That may seem absurd — 1996 was not even 30 years ago — but it is essential to remember how often Black history and queer history are erased. It is likely that Dunye was not the first Black lesbian director, but she is the only one we know of now.

Much of “The Watermelon Woman” deals with this issue of historical erasure as the film follows the story of Cheryl, a young Black lesbian filmmaker and a fictionalized version of Dunye herself. While watching the 1930s movie “Plantation Memories,” Cheryl is struck by the movie’s mammy character, played by a Black actress credited only as the Watermelon Woman. She decides to try and uncover the truth of the actress and create a documentary about her, and she discovers herself in the process.

University of Mississippi visiting assistant professor of film Juli Jackson described the significance of “The Watermelon Woman.”

“The film offers a nuanced portrayal of Black lesbian characters and explores underrepresented facets of the Black experience through the unique lens of mockumentary filmmaking. The work also showcases numerous innovative elements … fictional media like films, VHS tapes, photographs, etc., crafted by Dunye as a way of documenting lost LGBTQ+ history of the period,” Jackson said. ‘The Watermelon Woman’ deserves all the praise heaped onto it.”

The film deals heavily with the topic of on-screen racial representation. One character, Cheryl’s friend Tamara, asks why she is so obsessed with an actress who played racist roles; but for Cheryl, these are the only ways in which she can see herself reflected on the screen, no matter what role she plays.

With this in mind, it is no surprise that the truth of Fae Richards — the true name of the eponymous Watermelon Woman — does not come easy. Searches for Richards turn up empty, white lesbians and lesbian archivists are hostile to Dunye and treat Black and Black lesbian history with little care and Dunye is consistently spoken over and ignored by white people in her life, whether or not they claim to fight on her side.

Alongside uncovering the Watermelon Woman’s hidden history, Cheryl must deal with challenges in her day-to-day life. Cheryl is profiled and accosted by cops, and her white girlfriend refuses to defend her when a woman she is interviewing spews racist remarks. At every turn, Cheryl is met with reminders that even in lesbian circles, she feels different.

But then, the frustration and loneliness that she feels shows up in Fae’s life as well. In order to get in with Hollywood, Fae dated a notoriously harsh white director named Martha Page. Whether or not there was real affection there proves irrelevant, as Martha fails to make Fae a star, only casting her in stereotypical Black roles and never crediting her under her real name.

Until Cheryl finds her, the Watermelon Woman is an invisible character, just as Black lesbians had been invisible until Dunye directed “The Watermelon Woman.” There is hardly a record of Fae and no books are written about her, outside of the women who knew and loved her: the other Black women and lesbians in her life.

Fae’s life partner, another Black woman, tells Cheryl, “If you are really in the family, you will always understand that our family will only have each other.”