Uncertainty about the legal standing of House Bill 1193 — which would prohibit Mississippi public schools from teaching about diversity, equity and inclusion-related topics, specifically sex and gender, race and DEI-supporting programs — has left many University of Mississippi professors uncertain about how to proceed in the classroom.

Last month, United States District Judge Henry T. Wingate issued a preliminary injunction blocking the law’s enforcement while the case proceeds in court. The judge found that the law violates the First and Fourteenth Amendments by infringing on free expression and causing injury to educators and students.

UM faculty have expressed concern over whether they should make adjustments to course content to accommodate the law, which was signed into law by Gov. Tate Reeves in April.

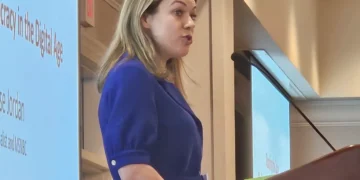

“The stipulation against DEI programs and hiring practices is problematic,” Deanna Kreisel, an associate professor of English at the university, said in an interview with The Daily Mississippian. “It prevents the university from addressing long-standing patterns of discrimination and ensuring an even playing field for job applicants and other members of the university community.”

Since Wingate’s ruling, the university has not publicly provided further guidance to faculty and staff.

“The university is monitoring the case to ensure that we are complying with the law as it works its way through the court system,” Jacob Batte, director of news and media relations at UM, said in an email to The Daily Mississippian on Sept. 10. “The university monitors legislative and legal matters closely and provides updates to campus leaders when appropriate.”

Cliff Johnson, a UM law professor, worries that his curriculum may violate the new ban.

Johnson told the Associated Press that he and his students often discuss what could be considered “divisive topics” and added that he did not believe that the law would allow him to teach about the First, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments in the U.S. Constitution.

“I think I’m in a very difficult position,” Johnson said. “I can teach my class as usual and run the risk of being disciplined, or I could abandon something that’s very important to me.”

Kreisel agrees that the vagueness of the bill leaves uncertainty regarding classroom instruction.

“Unfortunately, the bill is very vague and confusingly worded, and (it) has already had a profound, chilling effect on campus speech and teaching,” Kreisel said. “Many faculty are very concerned that the way that they normally teach their subject material could be literally against the law. … I might very well have to rewrite lectures that mention gender and race and essentially censor my pedagogy in order to comply with the law — as will every single faculty member.”

Previously, the university released statements on other measures restricting DEI.

“We have taken steps to align the university’s strategic initiatives and will continue to review our programs and make adjustments if necessary,” Batte said in response to the U.S. Department of Education’s statement in February indicating schools risk losing federal funding if they continue to take race into account in all aspects of student, academic and campus life.

In August, lawyers made their cases in court against the state bill on behalf of parents, students and professors who opposed the DEI ban.

According to Mississippi Today, the attorneys said that “the law would ban discussions and books about the Civil War, women’s rights and slavery.”

“I cannot overstate how damaging and far-ranging the effects could be on students if the law is allowed to stand,” Kreisel said.