College athletics are on the cusp of the biggest transformation since the National Collegiate Athletics Association was created in 1906.

A proposed settlement of the landmark House v. NCAA case, which includes a resolution of three antitrust lawsuits filed against the NCAA and power athletic conferences, clears the way for schools to begin paying players directly through revenue sharing starting as early as 2025.

The resolution received preliminary approval by a federal judge in October 2024.

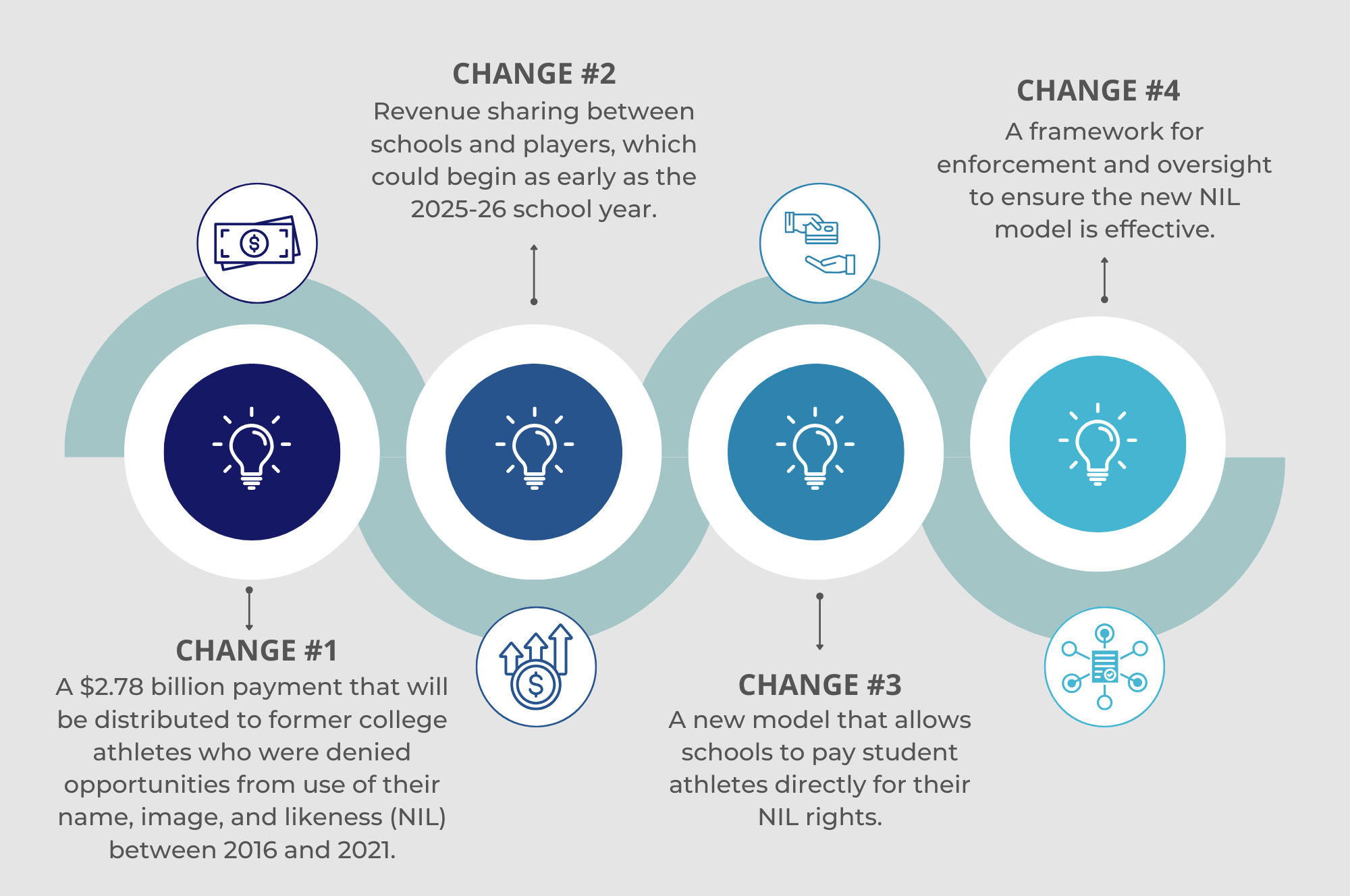

The agreement designates $2.78 billion in retroactive payments to former college athletes dating back to 2016 who could not earn compensation from name, image and likeness (NIL) deals. It also allows college athletic departments to make revenue sharing agreements with players. And in an effort to eliminate pay-for-play payments that have become commonplace among booster-led NIL collectives, the settlement facilitates the establishment of an enforcement agency by the NCAA and power conferences to ensure the new NIL model is implemented consistently.

Indirectly, the settlement further advances the idea that amateur student athletes could be considered university employees.

“I think the amateurism model is gone,” Associate Dean for Research and Montague Professor of Law at the UM School of Law William Berry said. “When the House settlement becomes final, we’re going to have revenue sharing, and so I think the student athlete model is essentially dead if the House settlement goes through.”

The lawsuit was filed in 2020 by former Arizona State swimmer Grant House and Sedona Prince, a former Oregon and current TCU women’s basketball player, who alleged the NCAA’s rules violate antitrust laws and exploit student athletes. The plaintiffs claimed that the NCAA’s restrictions on NIL payments and control of TV profits prevent athletes from realizing their true market value.

A final hearing for approval of the settlement by Senior United States District Court Judge Claudia Wilken of the Northern District of California is scheduled for April 7, 2025.

Even after the House settlement is finalized, legal challenges may continue unless federal legislation outlines NIL rules, according to Brennan Berg, associate professor of sport and recreation at UM. Berg’s article titled “The Policy Discourse of Name, Image, and Likeness in College Athletics” was published last year in “The Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics.”

Photo courtesy: Brennan Berg

“Once this new system (dictated by the House settlement) gets put in place, it will get legally challenged. … I have a hard time imagining you have one lawsuit that is going to accommodate and represent tens of thousands of college athletes across the country,” Berg said. “I imagine you’re going to have a lot of college athletes who just say, ‘Hey, I’m aware of the House settlement, but that did not represent me or my interests. I had no say in it.’”

Commissioners of the Power Five athletic conferences — Atlantic Coast, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and Southeastern — helped craft the NCAA’s response to the lawsuit with input from school athletic directors.

“Judge Wilken has to go through different processes from a legal perspective, but they’re saying it will probably be next April or so before the final settlement,” Ole Miss Athletic Director Keith Carter said. “And that’s if there’s no hiccups and no roadblocks. We’re kind of preparing that revenue share (with players) would start July 1, 2025. … All of our legal counsel from the SEC office and outside legal counsel are confident and hopeful that it will settle in April or so.”

Legal precedent for House v. NCAA

The primary precedent for the House settlement was Alston v. NCAA. In that 2021 ruling, the Supreme Court rejected the proposition that the NCAA was immune from federal antitrust law and overturned NCAA rules that capped the amount schools can pay student-athletes for education-related benefits.

Prior to the Alston case, NCAA rules limited student athlete compensation to the cost of attendance. That included tuition, fees, room and board, books and other expenses. In the Alston ruling, the Supreme Court determined that schools could distribute as much as $5,980 a year to students in education-related compensation.

Alston v. NCAA should have served as a warning for what was to come in college sports. It laid the groundwork for future challenges to the NCAA’s restriction on student athlete compensation. Administrators in the NCAA and athletic departments simply were not prepared for a case like House v. NCAA.

“We probably should have (taken) a more forward thinking approach to this,” Carter said. “If we had gradually kind of worked toward this it probably would have been a much easier process, but now with the lawsuits and obviously with the things that are happening, it’s moving really fast.”

Unresolved legal challenges

In August 2023, Reggie Bush, a former Heisman trophy winner with the Trojans, sued the University of Southern California, the Pac-12 Conference and the NCAA for profiting off of his name, image and likeness without compensating him.

Bush and his attorneys are seeking compensation for years his name was used for marketing and to prevent his name from being used for financial gain without compensation again.

“This case is not just about seeking justice for Reggie Bush; it’s about setting a precedent for fair treatment for all college athletes,” Evan Selik, an attorney representing Bush, said. “Our goal is to rectify this injustice and pave the way for a system where athletes are rightfully recognized, compensated and treated fairly for their contributions.”

Four former University of Michigan players, including quarterback Denard Robinson and wide receiver Braylon Edwards, have filed a lawsuit against the NCAA and the Big Ten Network. They are seeking more than $50 million, saying they have been “wrongfully and unlawfully denied” the opportunity to earn money from their NIL.

The future of NIL

State legislatures led the charge for NIL compensation. California’s “Fair Pay to Play Act,” a statute that allows collegiate athletes to acquire endorsements while still maintaining athletic eligibility, was passed by the state legislature in 2019. To date, 32 states have passed NIL laws, most of them modeled on “Fair Pay to Play.”

Mississippi’s law allowing student athletes to receive compensation for use of their name, image and likeness went into effect on July 1, 2021.

Mississippi universities can place limitations on when student athletes can participate in endorsement-related activities, can control what athletes wear during university-sponsored events and can require athletes to notify their universities of any NIL transaction within three days of the agreement taking effect. State law also places restrictions on student athletes endorsing alcohol, tobacco, e-cigarettes or any other type of nicotine delivery system, sports performance-enhancing supplements or gambling and sports wagering.

Several federal bills that would regulate collegiate athletes’ compensation have been introduced by both Democrats and Republicans, but none have gained much traction in Congress. That means the House v. NCAA settlement, when finalized, would initiate the most transformative change to college athletics nationwide.

In the plan laid out in the lawsuit settlement, schools would be able to begin sharing revenue with players as soon as the 2025-26 school year. Twenty-four percent of the $2.75 billion settlement designated for former athletes will be taken from Power Five schools’ share of NCAA revenue and be paid to former college athletes who were deprived of NIL opportunities by the NCAA.

“The NCAA will pay (the $2.75 billion in back-pay to former college athletes). They will pay it out over a 10-year period,” Carter said.

But each university must determine how it will compensate players in the future.

“Obviously, we’re going to be in charge of figuring out how we pay the current rev share for the current student athletes starting in 2025,” Carter said.

Student-athletes are currently paid by NIL collectives, including the Ole Miss’ Grove Collective. However, with the settlement, student-athlete pay will likely shift to athletic departments, with funds coming primarily from donors and corporate sponsorships. This shift will give the departments more flexibility on how they can fund the revenue share.

For Ole Miss, Keith Carter wants to make sure The Grove Collective plays a role in the future of college sports.

Photo by Antonella Rescigno

“Whatever scenario plays out in the settlement, we know that we’re going to want to have Walker Jones (founder of The Grove Collective) and his team involved in our solution here at Ole Miss. We’re working almost daily on what that could look like,” Carter said.

Impact on Title IX

Every NCAA athlete, going back to 2016, will have the opportunity to participate in the revenue share. A plan for notifying every former NCAA athlete from 2016 on is currently being made.

“We will make sure that any athlete that we had at Ole Miss that fell into that window will have the opportunity to either opt-in or opt-out of the case,” Carter said. “Every school should definitely reach back and reach out to those student athletes.

Historically, Title IX, the law that prohibits discrimination based on sex in educational programs and activities that receive federal financial assistance, has dictated scholarship distribution among student athletes. It is not clear now that might apply after the House settlement. The money could be split 50-50 between women’s and men’s athletes, it could be weighted toward the sports that generate more revenue or it could be allocated according to another formula.

“It’s interesting to note that after the Supreme Court’s decision (in) Loper Bright last spring, administrative law is changing quite a bit, and it’s not clear to the degree which the Office of Civil Rights’ interpretation of Title IX is even applicable anymore,” Berry said.

In the case of Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts must exercise independent judgment when interpreting statutes, rather than deferring to government agency interpretations.

Congress may have to pass a new law to clarify how Title IX applies to the payment of athletes.

“It’s not clear what the law says about this kind of compensation because it has always been illegal and prohibited under NCAA rules. And so it’s not clear that Title IX is going to mandate anything. It’s not clear that Title IX applies to anything but athletic scholarships,” Berry said.

College athlete employee status

For years, some have said that college athletes should be considered employees because, while facing major risks by playing sports, athletes generate considerable income for institutions they represent.

On Sept. 29, 2021, the National Labor Relations Board published a memo stating that student athletes could be seen as employees under federal law, but the issue remains unsettled. If student athletes are given employment status, they also may be able to unionize and negotiate collective bargaining agreements.

“While players at academic institutions are commonly referred to as ‘student-athletes,’ I have chosen not to use that term in this memorandum because the term was created to deprive those individuals of workplace protections,” NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo wrote in the memo.

In July 2024, a U.S. appeals court in Philadelphia ruled in Johnson v. NCAA that athletes could not be barred from bringing Fair Labor Standards Act claims and remanded the case to a lower court to determine whether the athletes can be considered employees under the statute. The Fair Labor Standards Act sets federal minimum wage and overtime pay requirements for most private and public sector employees.

“With professional athletes as the clearest indicators, playing sports can certainly constitute compensable work,” U.S. Circuit Judge L. Felipe Restrepo wrote.

The NCAA has long held the position that student-athletes are amateurs who voluntarily participate in sports as an extension of their education, that they attend college for an education, not to be employed as athletes.

The NCAA says it has been expanding core benefits for athletes, from health care to career preparation, and wants to help schools steer more direct financial benefits to their athletes.

“A lot of the conversations I’ve had with people in Congress (who favor making athletes university employees) is: ‘The reason we’re interested in employment is because of the compensation questions,” NCAA President Charlie Baker told reporters in June. “If the court blesses (the House v. NCAA settlement), then it puts us in a position where we can go to Congress and say one of the three branches of the federal government blessed this as a model to create compensation without triggering employment.”

Even though a settlement of the House v. NCAA lawsuit could significantly transform the way schools compensate current and former student athletes starting next year, it likely will not be the final word on the issue. College athletics is a big money game, and more challenges over who gets compensated and how much they are paid are expected.

One thing is certain — the power of college players is growing stronger.