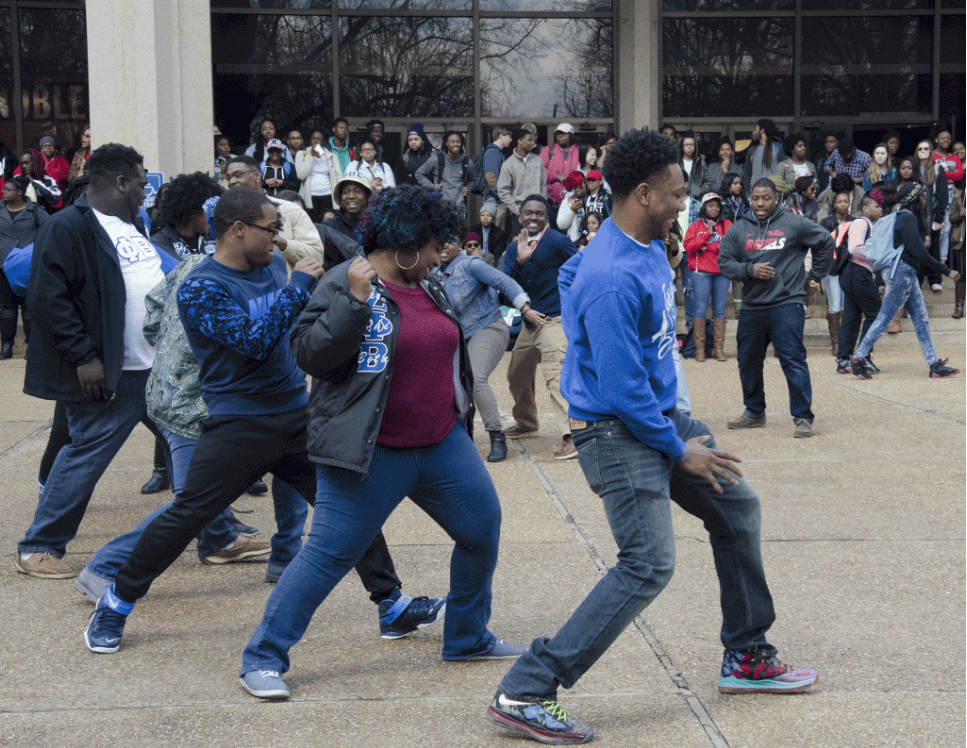

Music echoed throughout the University of Mississippi campus every Tuesday and Thursday during the fall of 2016. Synchronized claps, shouts and stomps permeated the damp Mississippi air, from the Paris-Yates Chapel to the Gertrude C. Ford Center. Blurs of vibrant pinks, reds, yellows, greens and blues captivated passersby traveling to and from class.

But when students returned from break in the spring of 2017, the campus was silent — save for the perpetually reverberating hum of construction equipment.

Seven out of nine nationally recognized historically black fraternities and sororities are currently represented on campus in UM’s National Pan-Hellenic Council community — Alpha Kappa Alpha, Delta Sigma Theta, Kappa Alpha Psi, Omega Psi Phi, Phi Beta Sigma, Sigma Gamma Rho and Zeta Phi Beta — and the Ole Miss Student Union, the hub of student life of campus since its creation, meant so much more to the Divine 9, as they are affectionately dubbed, than just a place to eat between classes.

“It was a home, a safe haven,” said Tommy Knight, president of the Eta Beta chapter of Phi Beta Sigma.

All of that changed when construction closed the student union in December 2016. The project broke ground in 2015, but “Union Unplugged,” performances every Tuesday and Thursday at the front of the building that often included NPHC “stepping” — traditional percussive dances performed by historically black fraternities and sororities — only halted when “Phase Two” of the expansion project began.

Construction on the union was initially scheduled to be completed earlier this year. It has been delayed yet again while going over its projected $60 million budget. The union is now set to open later in the semester and is “nearing completion,” according to a university press release issued on Monday.

Since construction on the union put a stop to “Union Unplugged” events, NPHC members have had to find new spaces on campus, like The Pavilion. However, there is a consensus that a feeling of unity and visibility has been lost.

“The prolonged construction has impacted NPHC organizations by taking away one of the venues that we could call our own, even if for only 45 minutes out of a week,” said Sumayia Young, president of Alpha Kappa Alpha’s Theta Psi chapter at Ole Miss. “Since ‘Union Unplugged’ was moved to The Pavilion, it lost a sense of community.”

She said the central location of the union was vital to the success of NPHC organizations and allowed everyone to take part in the “various festivities.”

Jarvis Benson, president of the University of Mississippi Black Student Union, isn’t a member of an NPHC organization, but he has noted that the “Unplugged” events are just not the same at The Pavilion.

“The Pavilion is far away from many parts of campus, so many are not able to make the trek to attend,” he said. “Keep in mind that NPHC organizations do not have houses on campus, so the spaces and times that they are able to gather on campus are few and far between.”

The lack of black spaces on campus is starkly clear when paralleled with the thick, white columns and deep red brick of Fraternity Row and Sorority Row, where decades-old mansions line the streets.

Knight said the lack of black fraternity houses makes him want to work harder for equal opportunities.

“It makes you envious, but at the same time, it makes you want to work,” he said.

Though it doesn’t compensate, the university completed construction on an NPHC Greek Garden in the spring of 2017. It is intended to serve as a symbolic space for the campus’s NPHC organizations, but many complain that it is too small and far away to occupy.

“It seemed as if (administration) tried to pacify us with the Greek Garden,” Young said.

Benson agreed that administration needs to put more effort into being inclusive of NPHC organizations and “make adequate steps to accommodate” them, while Knight wishes these groups had a “bigger space.”

“It seems the black community here is pushed to the side a little bit, even with the Greek Garden. ‘Be happy and have it,’ they said, but it’s all the way across campus,” Knight said. “With this being a predominantly white school, it’s important for us to know we have a voice, to know that we’re included.”

When Brian Foster, professor of sociology and Southern studies at the University of Mississippi, “crossed,” or was initiated, into Phi Beta Sigma’s Eta Beta chapter in 2009, he remembers the student union as a place where the black students of Ole Miss could build community.

“It was the epicenter, a central place for black Greek letter students socially and organizationally,” he said. “The union has been our ‘yard,’ where we do any number of things that are really vital parts to who we are, on a campus where that space has not always been promised.”

That’s not a coincidence, either.

According to Foster, black people have had to construct their own spaces to exist throughout history, making those spaces more meaningful to the people that inhabit them.

“We have had to move in and out of certain spaces to find community, to guard against the possibility of oppression, and to try to overcome inequality,” he said. “Creating a space where I can be whole, where I can be human, where I can laugh, where I can have fun, where I can build community — that is what ‘placemaking’ is, that’s what black people do. The Great Migration accomplished that, and at the micro level, the union accomplished that for a lot of NPHC members.”

Arthur Doctor, director of Fraternal Leadership and Learning and active member of historically black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha, said that it was expected that the union construction project would impact the “entire student population, not just one particular group.”

“The Student Union staff and other campus partners have been instrumental in working with the NPHC to continue traditions… to ensure that NPHC organizations can maintain a campus presence,” he said. “I believe our NPHC students are excited about the endless opportunities that the student union renovations will bring for them to engage with fellow students, while also providing venues for them to demonstrate pride in their organizations.”

However, Foster says the “construction is affecting (NPHC members) more than members of other Greek organizations.”

“The history of this campus manifests in the very terrain of the campus itself — what the campus looks like and the actual spaces and places that students have access to. We look on Fraternity Row, and we don’t see any housing or spaces for NPHC organizations,” Foster said. “Sigma Nu can do whatever in their house. NPHC members don’t have those same alternatives.”

Foster believes the way the NPHC organizations on campus have adapted to the union construction, though they shouldn’t have to, speaks to their resilience.

“I think the fact that we’ve shifted this space is an example of how, no matter what the terrain looks like, no matter what the environment is like, we will always find a way,” Foster said. “Y’all gon’ make it hard for us, but we’re still going to do our thing.”

The student union is the heart of every campus, and ours used to thud with the steps and strolls of black Greeks. For the foreseeable future, though, the only beats the campus will hear will be those of construction crews.